Interview (English version)

Question: On your website you’re telling that nature did help you to recover after the loss of your mother. Can you tell us more about that?

After my mother passed away, I ran from grief by burying myself in work. A bad relationship breakup complicated matters and I was in a dark place for a few years. I reached a point when I realized I had to do something about it, do something for other people, instead of being so focused on myself. It was affecting my family, my close friends and my health. So I signed up for a volunteer program in Tibet and this trip changed my life. Volunteers helped out at an orphanage in Lhasa and were taken to go sight-seeing in our free time. One such trip brought us to Lake Namtso. I was sitting by the edge of the lake when I experienced a sense of peace that had been eluding me for the longest time. The vastness of the lake reminded me how small I am in the scheme of the universe. Its beauty touched me and reminded me that life is beautiful, that there is just so much to live for and to explore. I got over myself and found hope.

I had a simple point-and-shoot camera to record my experiences working with the orphans but was intrigued by the digital SLR camera used by another volunteer. After the trip, I signed up for an online workshop to learn about F-stops and aperture, and later bought a digital SLR camera.

Question: “The Chinese idiom “天时地利人和” speaks to the importance of fortuitous timing (天时), favorable conditions (地利) and the human resolve (人和) to our endeavors.” How does this reflect on your photography?

Photographing nature and landscapes in extremely cold temperatures and waking up at insanely early hours (e.g. 2:30am during the summers) can take a toll on the body and mind. Often, I just want to sleep in but need to drag myself out of my warm bed. I think photographing requires self-discipline, determination and, in my case, a love of nature. If I’m not even out there, then there is no photograph to be made.

However, human resolve is just one part of the equation. Although I have become better at predicting when and where some of the natural phenomena, such as diamond dust, rainbow and mist, will appear as I accumulate experience, I am still unable to predict their occurrence with 100% accuracy. Luck continues to play a significant role in my encounters with nature. I have had many serendipitous encounters, where I find myself at the right place and at the right time, and am extremely grateful for them.

As an example of fortuitous timing, there was once when I went to photograph in the afternoon because I was feeling guilty for having enjoyed a long leisurely lunch, skipping photography. My afternoon exploration at a place near the restaurant brought me into contact with a large number of snowbugs. The timing was perfect. Had I gone there earlier, the snowbugs would not be backlit and would not be sparkling as they did when I saw them.

As an example of favorable conditions, there is a spot where the tip of trees will be selectively lit by the sun in the morning. During Autumn, I will visit this place whenever it rains overnight and the temperatures plummet because there will be a chance of mist appearing the following morning. However, 9 out of 10 times, the mist has turned out to be “not quite right.” This goes to show that although the place and the timing for the light are both right, I need nature’s cooperation to bring about the right conditions for the image to work (see image “Phantom”).

I see my photography as a continuous collaboration with nature.

Question: You live in Tokyo. For us that seems like a very busy place. Meanwhile, your images are calm and peaceful. Can you tell us more about that?

When I first moved to Japan, I worked for the Tokyo office of an American investment bank. After I left investment banking, I taught Japanese bankers English in person. During my free time, I flew over to Hokkaido or took the train to Aomori and Nagano to photograph.

I started renting an apartment in Hokkaido just when Covid started. The decision was prompted by the fact that hotels had been getting increasingly expensive and difficult to book due to the influx of visitors. It made more economic sense to rent a place. It proved to be a great decision because the hotels shut down for a few months due to Covid. Having my own kitchen meant I could cook, lowering the risk of infection.

Covid has brought my work online so it is now possible to photograph in the mornings, and teach in the afternoons and evenings. I now spend at least 5 months in Hokkaido each year and have been thinking of moving to Hokkaido for the longer term.

Question: Your images show small parts of nature. Often, you have to look twice before you see what is actually happening in your images. What is your idea behind this approach? What is your vision on photography?

I have to thank my mentor, Nevada Wier, for steering me away from larger landscapes. I started a mentorship with her through the Santa Fe Workshops after leaving investment banking. For about 2-3 years, I showed her my new images via Skype monthly. It was difficult to impress her with the larger landscape pictures because she had seen many similar images before, even if the locations were completely different. She has taught many people and has many photographer friends across different photography genres.

I found that she was impressed by the images that confused her, that required her to look twice, that involved me seeing and interpreting the scene. We all see and interpret the smaller details differently and are attracted by different subjects. I think her feedback biased me towards these images.

I am a rebel at heart in that I want to be different. I don’t want to end up with similar images as other people. There are many photographers and visiting photographers in Central Hokkaido. I see it as a fun challenge to produce something different from them, even if we end up at the same location.

Question: Your work is hard to pigeonhole (take that as a compliment ;) ). There seem to be influences from pointillism and there also seem to be elements from traditional Asian art. Some works seem almost painted or drawn and even vaguely reminiscent of comics. Can you tell us something about what has influenced your work according to you? (and how / in which work you see this)

People have mentioned that my images remind them of paintings. As a matter of fact, my first brush with the art world occurred when I chanced upon Monet’s “Impression, Sunrise” while shopping for a poster for my dormitory room in college. Intrigued by the image, I went to read up about Monet, Degas and other painters. The second poster that hung on my wall was Renoir’s “Bal du moulin de la Galette.” I next fell in love with Marc Chagall’s work for his bold use of colors and fantastical themes. I became a fan of Henri-Edmund Cross, a French pointillist painter after chancing upon his work at the Museum of Fine Art in Houston a few years ago. My latest love is Li Huayi, a contemporary ink painting artist from China. I like the simplicity and the meditative touch of his ink brush paintings. They reminded me of the Kungfu films I watched with my mother as a child.

When I was young, I danced ballet and read lots of fairytales. As I grew older, I became very fond of mysteries, stories with twists and turns, with plotlines that are not obvious. Agatha Christie, GK Chesterton and Roald Dahl were some of my favorites. I listen to music whenever I am driving to photograph. My mind gets really busy and often distracted, but music helps me to calm down and focus. When I am driving back after photographing, I’ll listen to an audible book to help me stay awake.

At first, these preferences and influences from childhood permeate through my work unconsciously. By that, I mean, I’m naturally drawn, for example, to scenes that resemble the backdrop of a ballet or a fairytale. But now, I pursue them a little more consciously.

Question: How do you find your subjects / images?

When I first started out photographing in Central Hokkaido, I visited iconic landmarks like a first-time tourist would. There are many famous lone trees here such as “The Christmas Tree,” “The Philosopher’s Tree,” (which was cut down around 10 years ago) and “The Seven Star Tree.” Although we can witness spectacular sunrises and sunsets at some of these locations, they tend to be more crowded. Also, the images from these locations turn out to be quite similar in terms of composition because there are only that many ways to photograph those lone trees. It often becomes a competition of “who was there when the sunrise / sunset was the most spectacular.”

As time passed, I made a conscious effort to avoid these low-hanging fruits, in search of more intimate landscapes. The “hit” rate was lower but it was more fulfilling when I made an image I liked. I also began to compose my images with a more conscious effort. I was keen to evolve. For example, when photographing trees, after taking a picture of what immediately leapt to my eyes and with the composition that instantly came to mind, I would try push myself to do something different. By something different, I meant something different from what I had done in the past or different from the other photographers’ images that I had seen on social media. I was keen to push the boundaries and break away from my habitual approach.

Also, I now focus more on pursuing scenes that touch me, that are more reflective of my likes, and hence more characteristic of me.

Question: You work in (ongoing) projects. What is the idea of working in (these) projects?

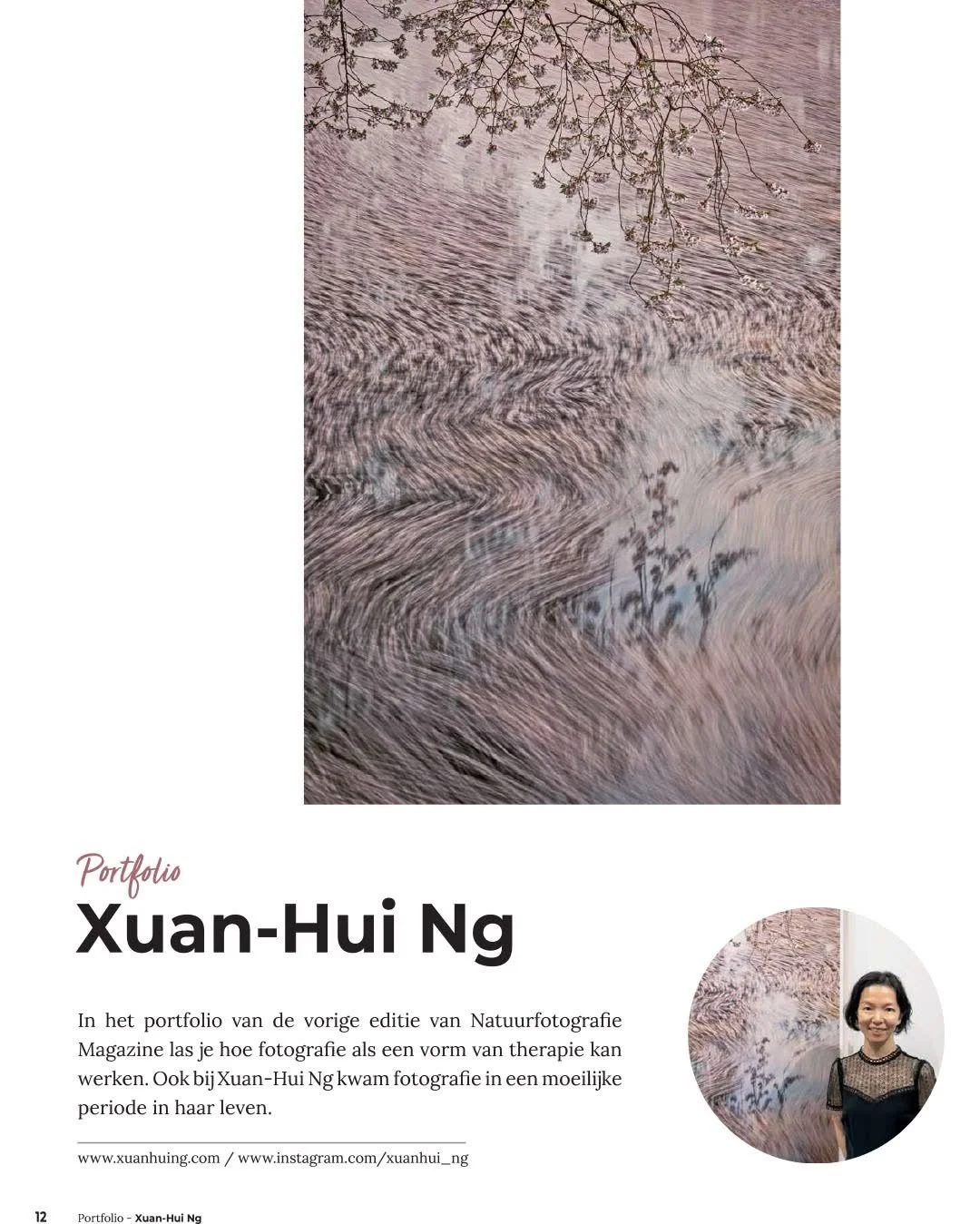

I think my projects are somewhat in chronological order, with the exception of Remembrance and Winter’s Coda. Remembrance is an ongoing project on cherry blossoms dedicated to my mother while Winter’s Coda is an ongoing project on the farmers’ practice of dispersing charcoal powder on snow to accelerate melting around mid-March.

Once I detect a shift or want to initiate a shift in my aesthetics, I move on to a different project. To be honest, I don’t think my projects make much sense. I think the projects of Samuel Feron, a French photographer whom I admire a lot, make much more sense. They are aesthetically and thematically consistent. The above said, I am not sure if the same approach will work for me. I need to meditate on this further.

Question: Your portfolio contains a lot of ice and snow. Is winter your favorite season?

Yes, winter is currently my favorite season. Snow simplifies the scene for me, as does fog. It’s the season when I have a chance to witness diamond dust / sun pillars and sun halos, and when shadows appear blue. I’m from Singapore, which is located near the equator. It has no seasons, and is hot and humid all year round. Perhaps that’s the reason why I appreciate ice and snow more, even though I suffer badly from cold hands and feet.

Question: Do you have a favourite image in this portfolio? What’s the story behind that image?

Remembrance #3 was one of the few images from my earlier photography days that managed to survive the test of time. I find that I often fall out of love with my images as my aesthetics evolve over time.

This photograph was taken during my first trip to Hirosaki in Aomori, Japan. I had been photographing for a few years in Hokkaido and was keen to explore other parts of Japan. The Hirosaki castle moat is lined with cherry blossom trees. Every spring, the fallen petals will carpet the moat in a sea of pink. I was keen to experiment more with long exposure and tried it with the fallen petals. The currents in the moat caused the petals to swirl in the water. I tried various compositions of the scene and finally settled on one that included the branch of a cherry blossom tree in the top of the image and swirls in the rest of the image.

I was quite pleased with the composition but pushed myself to continue exploring other compositions by inching to the right and left. While reviewing the images on my camera screen, I found that the composition with the reflection of the branch added an interesting touch to the image. This episode reminded me of the importance of experimentation and not resting on my laurels because I might find a composition that I liked even better than the previous.

Question: You’re also filming. Tell us more about that. Do you see it as an extension of your photography? Or does it have a completely different purpose for you?

I first created video clips to prove that diamond dust exists, that they are not a mere figment of my imagination. Now I create them in hope that they will bring the audience closer to the environment I was in when photographing. I have become more sensitive to the video potential of a scene. In general, I prioritize still images over videos. Many of these amazing natural phenomena are short-lived so I often take the still images first. If there’s time, I’ll move on to make the video clips.

However, over this past winter, diamond dust appeared in lower concentrations so making videos of it made more sense to me because even at very high shutter speed settings, I cannot come close to replicating what I saw. The videos did a better job at that.

The beautiful music you hear with the videos is written by Luca Longobardi, an Italian composer. I love his compositions and listen to them whenever I go out photographing. He has very kindly allowed me to pair my videos with his creations.

Question: Do you have a tip for our readers?

A valuable piece of advice I received from Masumi Takahashi back in 2010 was “to not be spellbound by the scenery and disregard the composition.” That’s something I hold close to heart even after so many years. It’s easy to be mesmerized by the various natural phenomena, such as aurora, rainbow and diamond dust, and end up just snapping away without giving much thought to composition. Many of these phenomena are transitory, which adds to our panic and haste. It’s important to take a pause to consider composition. If the composition doesn’t work, we must be brave enough to forgo the picture and look for a better spot or reframe it until we are satisfied. At the beginning, the phenomenon may disappear before we have a chance to make the image. However, as we learn to work faster under pressure, our ability to react quickly and eternalize these scenes will increase.

https://www.natuurfotografie.nl/